25 November 2025

Aline Duelen, Wendy Van den Broeck & Leo Van Audenhove

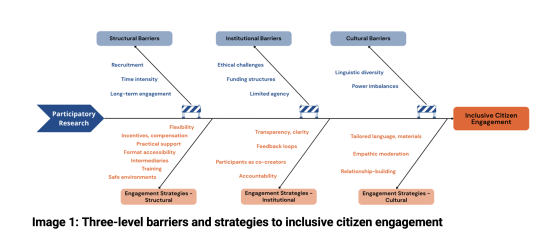

Across Europe and beyond, citizen participation has become a cornerstone of research and innovation policy. Governments, research institutes, and organizations increasingly engage citizens to co-create, test, and evaluate new solutions for social and technological challenges. Yet the promise of “research with and for society” is not always fulfilled. Too often, participation is limited to the same well-connected citizens, while those who face social, digital, linguistic, or economic barriers remain excluded. Inclusive participation is not just an ethical imperative. It strengthens the quality, legitimacy, and impact of research outcomes. In this policy brief, we highlight barriers and strategies to inclusive citizen participation, drawing on insights from expert interviews.

Highlights

| Even experts struggle with inclusion: Experts specialized in citizen participation report that inclusive engagement remains difficult, even with years of experience. Recruiting disadvantaged groups, sustaining involvement, and ensuring equal influence all require constant negotiation between stakeholders and adaptation of research practices. If inclusion challenges experts, it is clear that for researchers without this expertise, meaningful participation demands significant effort, time, and institutional support. |

| Barriers to inclusive participation run deep: Exclusion occurs on multiple levels and links to how research systems operate. Structural inequalities (e.g., sexism, ageism, racism, socio-economic status) limit disadvantaged citizens’ access and trust in government and research institutions, while institutional rules and short project timelines restrict flexibility, time, and resources in engaging vulnerable groups. Strict ethical procedures and funding models that prioritize outputs over relationships further undermine citizen participation. Overcoming these barriers requires more than improved recruitment; it demands systemic change in how research is organized, funded, and evaluated. |

| Inclusion is not a one-off intervention: Inclusion cannot be achieved through short consultations or isolated workshops. It is a gradual process that evolves through trust, reciprocity, and continuous engagement between researchers and citizens. Experts stress that short project cycles and rigid funding models undermine this process. To foster meaningful participation, funding and ethics frameworks must support slower, relationship-based approaches that prioritize trust and mutual learning over quick results. |

| Shared responsibility is key to change: Inclusive citizen participation cannot rely on researchers’ individual motivation alone. Policymakers, funders, institutions, and community organizations all share responsibility for creating accessible and empowering research environments. Experts emphasized that true inclusion requires coordination across these actors, supported by flexible frameworks, capacity building, and institutional incentives that value time invested in relational and inclusive work. |

1. Why inclusion matters

Citizen participation strengthens both the quality and fairness of research. Yet, many groups remain systematically excluded due to digital, linguistic, social, or economic barriers. Inclusion is not only an ethical responsibility, it is a driver of better research and innovation outcomes. Policymakers and institutions should therefore treat inclusion as a structural requirement rather than an optional add-on, embedding it into every stage of research design, implementation, and evaluation. Inclusive research goes beyond inviting citizens to comment or provide feedback. It involves recognizing people’s lived experiences as valuable knowledge that can shape both the process and the research outcomes. When citizens participate meaningfully, research becomes more democratic, relevant, and socially robust. It helps prevent bias, strengthens public trust, and leads to more sustainable and socially accepted solutions. Moreover, inclusive participation gives citizens a sense of ownership over the changes that affect their lives.

Despite these benefits, many research initiatives still struggle to reach people who are facing barriers such as limited digital access, language difficulties, disabilities, or economic insecurity. As a result, the perspectives of those most affected by inequality or technological change remain insufficiently reflected in the research and evidence that shape public policy and innovation agendas. Experts point out that inclusion is hindered by structural inequalities, institutional constraints, and cultural dynamics that too often go unnoticed in research design. Achieving meaningful participation, therefore, requires deliberate action at every level, from national policy frameworks to everyday research practice.

Moving toward genuine inclusion also requires a fundamental shift in mindset. Citizens must be regarded not as passive subjects or “end users” but as co-creators and partners in knowledge production. This shift takes time, sustained commitment, and institutional structures that value social engagement as much as scientific excellence. Too often, participation remains symbolic, a box to tick rather than a shared process of knowledge creation. Giving citizens real influence over research agendas, methods, and outcomes transforms research from extractive to collaborative, making it more democratic, equitable, and impactful for society as a whole. Meaningful engagement has proven benefits. When citizens are genuinely involved, projects gain richer insights, improved policy translation, and stronger community trust. Inclusive approaches consistently produce research that is more relevant and legitimate. Investing in inclusion is therefore not only fair, it enhances both the scientific and societal value of research.

2. Understanding the barriers

Structural barriers such as recruitment, time intensity, and long-term engagement stem from broader social inequalities and are linked to access and recognition. Recruitment often fails to reach marginalized communities, especially when invitations rely on online platforms or formal networks. Time and resource constraints make it difficult for citizens juggling work or care responsibilities to take part. Many also have limited trust in and skepticism towards research institutions and government, leading to the idea that their voices will not matter anyway.

Institutional barriers such as ethical challenges, funding structures, and limited agency arise from the way research is organized and funded. Ethics procedures, while essential, are often rigid and designed for traditional studies rather than participatory projects. Informed consent templates, designed to protect participants’ rights, can be too complex for individuals with lower literacy levels. Funding models prioritize outputs and efficiency over process and relationships. In some projects, citizens’ contributions are confined to the early stages of consultation, while final decisions remain in the hands of professional researchers, stakeholders, or policy makers. This imbalance risks turning participation into a symbolic and tokenistic exercise rather than genuine collaboration.

Cultural barriers such as linguistic diversity and power imbalances occur in everyday communication between researchers and citizens. Academic language can be inaccessible or intimidating. This can already form a barrier in the recruitment phase, in the style and tone of the invitation to participate. Social hierarchies, differences in confidence, and contrasting communication styles can silence certain voices in group settings. In individual interviews, participants can lean towards more socially desirable answers rather than sharing their actual opinions and experiences. Without careful facilitation, those already comfortable in research environments dominate discussions, while others withdraw or self-censor.

3. Strategies for inclusive citizen participation

Despite these obstacles, inclusive citizen participation is achievable when researchers and policymakers commit to deliberate, reflective strategies. The following approaches, drawn from expert insights, illustrate how inclusion can move from aspiration to reality.

Addressing structural barriers

At the structural level, the focus is on access and recognition. Fair compensation for citizens’ time, through payments, vouchers, or even shared meals, signals respect and lowers economic barriers. Flexibility in scheduling and location helps accommodate participants’ personal circumstances. Engagement sessions held in community centers, libraries, or familiar local venues create a more relaxed environment than university buildings or offices. Providing practical support, such as childcare, transport assistance, or digital access tools, can further remove logistical obstacles. Experts also emphasized the value of trusted intermediaries, such as community leaders, NGOs, or local associations, who can connect researchers with underrepresented groups and build trust over time. Short training or orientation sessions before participation can also empower citizens who may feel unqualified to contribute, boosting confidence and ownership. As one expert explained, “Not everyone starts from the same comfort level with research methods or technology. A little preparation can change how people engage.”

Overcoming institutional barriers

Institutions and funding bodies play a decisive role in enabling or constraining inclusion. Transparency and clarity from the outset are essential. Citizens need to understand what a project aims to achieve, what their role will be, and how their input will make a difference. Clear communication builds trust and manages expectations on both sides. Creating feedback loops is another cornerstone of good practice. When participants see how their perspectives shaped the final results, whether it is through reports, videos, or community events, they feel that their voices matter. This also increases accountability for researchers and funders. Viewing citizens as co-creators rather than mere informants helps balance power relations. This requires researchers to let go of control and share ownership of decisions. Ethical frameworks and funding rules should recognize this shift by allowing more flexibility, longer timeframes, and adequate resources for engagement. Researchers also bear a duty of advocacy and accountability: ensuring that citizens’ contributions are respected within institutions and that results are disseminated in accessible ways.

Tackling cultural barriers

Inclusive citizen participation depends heavily on how interactions are facilitated. Researchers should use clear, plain language and avoid academic jargon. Where necessary, materials should be translated or supported with visuals and examples drawn from citizens’ daily lives. Empathic moderation is equally important. Facilitators who approach discussions with openness and humility can build bridges across social and cultural differences. Sharing small personal stories or moments of vulnerability helps dissolve hierarchical boundaries. Inclusion also requires long-term relationship building. Trust grows when citizens see researchers returning, listening, and acting on feedback, not just collecting data and disappearing. As one expert noted, “People open up when they feel seen, not studied.”

4. Policy and practice implications

Inclusive citizen participation requires all actors in the research ecosystem to take responsibility. Policymakers should embed inclusion into funding rules, ethics procedures, and evaluation criteria, ensuring that projects have the time and resources to build trust and sustain engagement. Research institutions must value participation as legitimate scientific work, offering training in facilitation and co-creation, and rewarding high-quality engagement alongside traditional outputs. Community organisations and citizens play a central role by shaping priorities, identifying local needs, and ensuring that research translates into meaningful improvements.

Moving from symbolic involvement to participation that genuinely shapes research requires a shift in how success is understood. Inclusion is not a quick fix but a long-term practice built on mutual respect, adaptability, and shared ownership. As societies confront major challenges such as digitalisation, misinformation, and climate change, the need for research that reflects the voices of all citizens becomes urgent.

We therefore propose the following concrete recommendations for inclusive, successful, and sustainable citizen engagement:

| Embed inclusion in funding and evaluation criteria Make inclusion a formal requirement in research funding calls and evaluation frameworks. Projects should demonstrate concrete plans for engaging diverse citizens and allocate specific resources (time, budget, and expertise) to support this work. |

| Support long-term and relational research models Funders should move away from short project cycles that undermine trust-building. Longer-term funding and flexible timelines are essential to maintain meaningful relationships with communities and avoid tokenistic engagement. |

| Reform ethical and institutional frameworks Adapt ethical and administrative procedures to fit participatory research realities. Simplify consent and reporting processes, recognize community partners as co-researchers, and allow adaptive methods without penalizing flexibility. |

| Build capacity for inclusive engagement Provide training, tools, and mentorship programs that equip researchers with practical skills in communication, facilitation, and co-creation. Institutions should reward engagement work equally to academic outputs to encourage genuine participation. |

| Strengthen cross-sector collaboration Encourage partnerships between policymakers, researchers, civil society, and local organizations to share responsibility for inclusion. Collaborative networks make it easier to reach underrepresented groups and sustain engagement beyond individual projects. |

This policy brief summarizes findings from the study Participation that Matters: Expert Insights on Designing Inclusive Living Labs (imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, 2025).